Richard Wagner (1813-1883) -- An illustrated biography by Vincent Vargas |

|

Part Three: Revolutions Around the time of the completion of Tannhäuser, Wagner had begun to be absorbed by Greek drama. In particular, he was mesmerized by the Oresteia of Aeschylus, with its bloody re-telling of the homecoming and murder of King Agamemnon and Orestes' flight from the avenging Furies. Throughout the writing of his next opera, Lohengrin, Wagner read and re-read the classics voraciously. He was coming around to accepting the Greek theory that the myths of a given people provided the most fitting dramas, and he was becoming convinced that by adapting Germanic legends and medieval poetry, and transforming them into modern music drama that he was essentially involved in the same creative process that had led the Greek dramatists to the creations of those classic tragedies thousands of years ago. More than one hundred years later, when Wieland Wagner, the composer's grandson and artistic director of the Bayreuth festival, wanted to rid his grandfather's works of all things Teutonic after World War II, he staged these operas using sets and costumes that owed more to Ancient Greece than to Medieval Germany. During the years 1845 to 1848 Wagner was busy writing and making artistic decisions that would change the rest of his musical life many years later. In 1845 Wagner wrote a libretto dealing with another song contest (Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg). At the same time, he had discovered Jacob Grimm's Deutsche Mythologie, and had gone on to study the German epics, the Scandinavian eddas, and many other volumes of Nordic mythology. The medieval poet Wolfram von Eschenbach, whom Wagner had already immortalized as a character in his opera Tannhäuser, became one of the composer's favorite writers. Based on his reading of Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival, he wrote prose sketches to two operas that he would eventually complete, Lohengrin and Parsifal. He decided to set Lohengrin to music first, a task that he began on April of 1846. On April 28, 1848 Wagner completed the composition of Lohengrin. He then went on to write the libretto to a work that at first he called Siegfrieds Tod (Siegfried's Death) and that much later would become Götterdämmerung. |

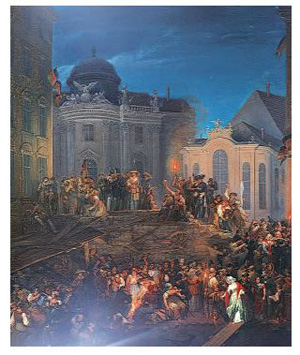

In 1848, a popular uprising in Germany and Austria against the autocratic powers of royalty sparked a revolution in many cities and towns, among them in Dresden where Wagner became one of the uprising's chief supporters. The people took to the streets and pressed the king with their demand for electoral reform and social justice. Wagner put his career and position as Royal Kapellmeister in jeopardy by writing an article in which he envisioned the downfall of the aristocracy. Caught up in the revolutionary fervor, Wagner began to see a parallel between the political upheavals of his time and the musical upheavals to which he was significantly contributing. He wrote inflammatory tirades published anonymously in a republican journal, personally distributed manifestos to the Saxon troops, and exposed himself to fire in the tower of the Kreuzkirche on May 7, 1849, where he posted himself to spy on the troops below. On the sixteenth of May, a warrant for his arrest was issued by the authorities. The warrant mentioned that the composer was to be seized immediately and held for interrogation concerning his unlawful participation in the revolutionary activities that had taken place in the city. Luckily for Wagner, the search warrant issued by the Saxon authorities was hastily written and was not too precise when it came to the composer's description. It described Wagner as "37 to 38 years old, of medium height, with brown hair and eyeglasses." Given this flimsy description, it was easy for Wagner, who had not yet achieved fame at this time, to completely elude the authorities. Eventually, with the financial assistance of his friend and future father-in-law Franz Liszt, Wagner managed to escape Dresden, and he was able to travel to Switzerland via Paris. |

|

While living in exile, Wagner attempted to earn his living as a writer. It is at this time that he produced some of his most important theoretical writing about music and theater. "Art and Revolution," "The Artwork of the Future," and "Opera and Drama" were all written during his years in exile. These works provided the theoretical background for the later Wagnerian music dramas. These revolutionary years also stimulated Wagner's musical creativity. By April 1848 Lohengrin was completed, and the concept of the Ring of the Nibelung began to take on a more concrete form. While he was involved planning what would become his mightiest work, Wagner also developed ideas for operas based on several historical and mythological characters. He wrote sketches about a possible stage work based on the myth of Achilles, another on the life of medieval emperor Frederick Barbarossa and another about the life and ministry of Jesus Christ. Before leaving Paris for Switzerland in 1850, he also worked on drafts for an opera based on a smith who forges a sword and a ring, and escapes from his enemies through the power of his art. The work was called Wieland der Schmied (Wieland the Smith), and it already contained some of the seminal elements of the Ring. Lohengrin was given its world premiere at the Weimar Court Theater on August 28, 1850 under the direction of Wagner's friend Franz Liszt. Wagner himself, banned from Dresden, was unable to be present at the performance. The opera proved to be a great success, and Wagner's name began to be mentioned in the same breath as the established composers of the day. The success of Lohengrin also ensured Wagner's definitive breakthrough as an innovative opera composer, and it inspired him to work with ever greater intensity on the realization of some of his other more innovative projects. The revolutionary firebrand had become Europe's most celebrated composer. As a result of his great success he was granted partial amnesty in 1860. In March 1862 Wagner applied for a full amnesty to the King of Saxony and was granted his request. However, there was now another royal court that began to interest him much more than that of Dresden: the court of King Ludwig II of Munich. |

|

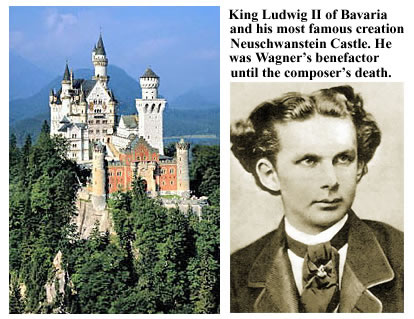

Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria attended his first performance of an opera -- Lohengrin -- at the age of fifteen. He cried tears of rapture during the performance. The work became the basis for his private psychological fantasy world to which he would often escape in his adult life. His obsession with Wagner's operas led him to order the construction of various fairy tale castles. The beautiful Neuschwanstein is most likely the best known of the Wagner-inspired structures. When Ludwig was crowned King of Bavaria, one of his first administrative functions as monarch was to have his cabinet secretary find Richard Wagner and bring him to his court. The composer was back in Germany at this time, broke and hiding from his creditors. On May 4, 1864, the eighteen year-old king and the fifty-one year old composer met for the first time. It was the meeting of two worlds. On one side stood the dreamy boy king, the mad king, and on the other the tempestuous middle-aged composer who, tired of running from creditors, was ready to settle down to a life of public recognition, and personal artistic accomplishment. Wagner quickly realized that King Ludwig was enchanted by the composer, and he was not about to disappoint his new patron. |

When King Ludwig expressed a fervent interest in financing a new opera composed by Wagner, the composer was not shy about agreeing to the offer. For King Ludwig, Wagner proposed a mad opera. It was the perfect complement for a mad monarch. The king agreed to finance the entire project. Tristan und Isolde was the first collaboration between the two men. Many of their surviving letters show the extent to which King Ludwig worshiped the composer. As the impossibly difficult rehearsals of Tristan und Isolde were underway, and as opening night in Munich was getting closer, King Ludwig wrote to Wagner: "My heart gives me no peace...nearer and nearer draws the happy day -- Tristan will rise! We must break through the barriers of custom, shatter the laws of the base world! The ideal must come to life! We shall march forward conscious of victory. My loved one, I shall never forsake you! Oh Tristan, Tristan will come to me! The dreams of my boyhood and youth will be made real..." |

|

Long before King Ludwig rushed to Wagner's rescue, and ultimately took on the financial responsibility of staging the new work, the composer also had the support from other members of royalty in Europe as well as in the New World. Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil was an avid Wagner enthusiast and a learned music lover. During the composer's difficult times of exile and political persecution, when money was scarce and the incentive to go on as a composer was difficult, Dom Pedro wrote a letter to Wagner expressing his interest for him to write an opera for the Italian Company in Rio de Janeiro. The offer stipulated that Wagner was to have whatever sum he named. He offered him a suite in his palace when Wagner was exiled from Bavaria, and in a handwritten plea prompted the composer to finish Tristan und Isolde. Dom Pedro then went on to personally invite him to come to Brazil to conduct the work himself. The offer was tempting but Wagner foresaw the hopelessness of trying to get Italian opera singers to perform the kind of music-dramas that he was about to write. He declined the offer. Nevertheless, Dom Pedro’s friendly overtures shaped his private resolution; and, as he told Franz Liszt in the summer of 1857, he finally determined to give up his headstrong design of completing the "Ring," and set to work seriously upon Tristan und Isolde. |

Tristan und Isolde was the most complex opera written at the time and it remains one of the most intricate works in the canon. Born out of the composer's new theories of composition, fueled by his love for Mathilde von Wesendonck, the beautiful wife of a wealthy silk merchant of Zurich who helped Wagner through one of his many financial crises, and deeply influenced by the dark, pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, the work proved to be the pinnacle of the Romantic movement, and at the same time, its ultimate challenge. As composer Richard Strauss wrote: "Tristan und Isolde marked the end of all romanticism. Here the yearning of the entire 19th century is gathered in one focal point." Tristan und Isolde is a turning point not only in opera, but in western art and music. Leave it to Wagner to bring a movement to its zenith and then turn around and destroy it. Wagner conceptualized the opera in the autumn of 1854, with the earliest sketch dating back to December, 1856. He completed the prose poem for the opera in 1857 and completed the composition of the music between 1857 and 1859. Writing this work must have been difficult, but getting it performed proved to be a truly monumental task. In 1859, while Wagner was living in exile in Paris, he attempted to secure a theater for the premiere performance of Tristan und Isolde. No opera house in Paris would take the work, but after explaining to the Dresden Opera the work's simple needs (very little chorus, few principals, and three simple acts), Wagner found a home for the premiere. However, after seventy-seven rehearsals and extreme stress upon the tenor, the work was declared un-performable and was abandoned. |

|

King Ludwig, of course, ended up financing the premiere at the Munich Royal Court Theater in 1865. The orchestra was so large that some of the seats in the front of the theater had to be removed to accommodate all the musicians. Horrified at the eroticism, men at the premiere removed their wives from the theater, and a priest was seen crossing himself before making a hasty retreat from the performance. The first performance of Tristan und Isolde was conducted by Hans von Bülow, one of composer Franz Liszt's students. By 1862, Wagner and his wife Minna had parted. The stormy marriage had produced no children, and she died a year after the first performance of Tristan. Wagner had not only had a passionate affair with Mathilde von Wesendonck (the inspiration for Tristan as well as the amazing Wesendonck lieder) but was passionately involved with von Bülow's wife, Cosima, who was Franz Liszt's daughter and twenty-four years younger than the composer. It was a well-known fact that Wagner and Cosima were lovers, and the hapless von Bülow not only allowed it to happen but condoned it. When eventually Cosima separated from Hans von Bülow and married Wagner, she wrote in her diary words that could have easily come from the libretto of Tristan und Isolde: "My love became for me a rebirth, a deliverance, a fading away of all that was trivial and bad in me, and I swore to seal it through death, through... complete devotion." The first Tristan and Isolde were Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld and his wife Malwine. They received 2, 800 guilders for their initial performances of this work. Three weeks after the last performance of the opera, Ludwig died in Dresden. Many felt that the strain of the role killed the opera singer. Now that Tristan was complete, Wagner set himself to finish the monumental Ring of the Nibelung, a work the likes of which had never been composed, and which needed a theater the likes of which did not exist. The previous years of his life had been filled with the revolutionary innovations that had set the world talking, and more often than not, arguing about him and his music. The next decades of his life would prove to be the most prolific and revolutionary of all. |