Richard Wagner (1813-1883) -- An illustrated biography by Vincent Vargas |

Part Four: From Bayreuth to Venice Wagner's technically challenging works always proved difficult for the average 19th century opera house. This lack of resources often enraged the composer who dreamed of presenting his works in a theater where proper stagecraft and adequate amounts of time for rehearsal would be the norm. On the day of his fifty-ninth birthday, Wagner saw workers lay the foundation-stone of the Festspielhaus, a new theater atop the so-called Green Hill outside Bayreuth, a sizable city in upper Franconia, in a valley between the Franconian Jura and the Fichtelgebirge Mountains.

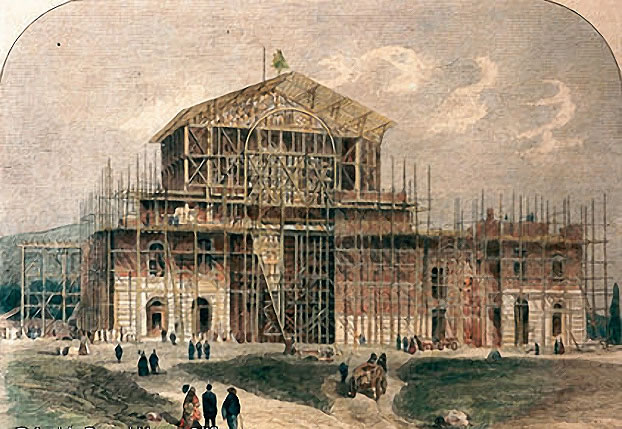

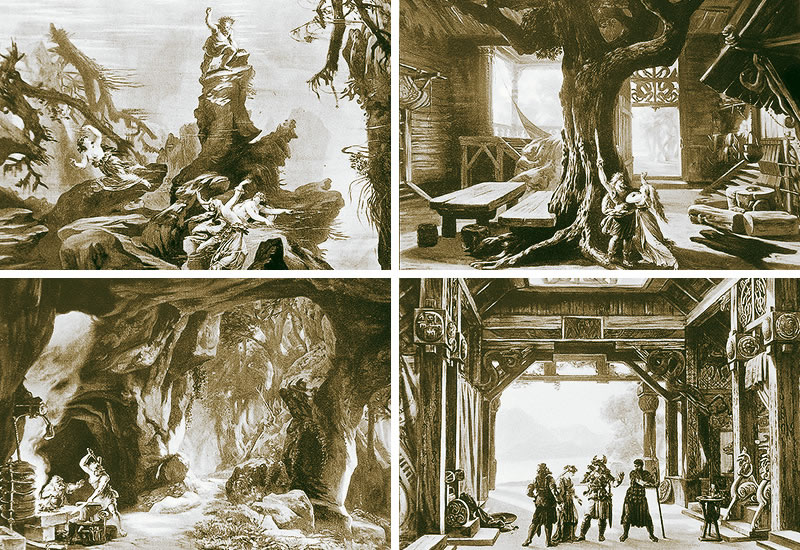

The city of Bayreuth had always fascinated the composer because of its lavishly ornate Margravial Opera House which had been built between 1744 and 1748. It was one of the few surviving Baroque theaters of its time, and it is still standing today, very much the way he knew it. Wagner was well acquainted with the theater, having conducted there many times. The "Markgräfliches Opernhaus" was the kind of over-the-top Baroque place that the composer hated, filled with boxes from which you can see and be seen, and which promoted the very worst in class distinction. There was one aspect of the theater, though, that Wagner loved: its incredibly deep stage. At 27 meters it was perfect for the grandiose musical dreams that in his youth were already taking shape. As The Ring of the Nibelung was progressing from mere ideas to a series of libretti and actual notes on paper it was key to have a theater that had this kind of deep stage. When Ludwig II of Bavaria appeared on the scene, willing and monetarily more than able to pay for a new opera house for his favorite composer, Wagner dropped his plans of making the Margravial the place where his Ring would premiere, and he put his mind to making sure that the new theater rising on the hill north of the city was everything he ever dreamed of. The entire project, based on an unrealized Munich opera house by Gottfried Semper, was entirely supervised by the composer, and largely paid for by loans from King Ludwig. Although the composer also had to do many exhausting concert tours in order to raise money for the completion of the building. The most revolutionary aspect of this new theater was going to be its sunken orchestra pit, hidden completely from the audience, and thus unable to break the illusion of the drama onstage, since no interfering light or sight of the musicians was possible. In Wagner's dream the music would just filter in from under the stage, and fill the wooden structure, surrounding the public with sound. The dream became a reality soon enough. The Festspielhaus was completed in time for the premiere of The Ring of the Nibelung from August 13 to the 17, 1876. One can only imagine what the first Ring cycle must have been like in the newly-built theater. Certainly there had been a great deal of time devoted to the work: two full summers. The initial rounds of rehearsals began on July 1, 1875. Conductor Hans Richter conducted all four operas, but Wagner micromanaged the entire rehearsal process. The most difficult aspect of the rehearsal period for the composer was making the singers subjugate themselves to the roles. In the meanwhile costumes and sets were coming in with each opera offering such monumental challenges, as far as the staging was concerned, that it was any wonder how the whole thing finally came together. Wagner's score might have been the music of the future, but he was very much bound by the limitations of nineteenth century stagecraft. For the first scene of Das Rheingold a special machine was devised by Carl Brandt that made the Rhinemaidens seem as if they were swimming. Likewise, it was reported in the press that the serpent in the later scenes of the first opera was a masterful piece of stagecraft. Other effects, however, did not go so well. The dragon in Siegfried was built, as was most of the scenery and effects, in England and it was shipped in pieces to Germany. Unfortunately, the neck, the part that gave the figure its most natural movement, ended up on opening night not in Bayreuth but in Beirut. As a result, the dragon probably ended up looking quite ridiculous. King Ludwig was most generous during the entire rehearsal process and even presented Wagner his beloved black stallion Cocotte. The horse was cast as Grane, and made his acting debut at the Ring premiere. For a complete list of the cast of the first Ring Cycle, as well as pictures from that production, you can visit the Productions section of this site by clicking here. (Below: Four scenic designs by Viennese landscape artist Josef Hoffmann. The sets of the first Bayreuth production were based on his work. Clockwise from upper left: Das Rheingold, scene one, Die Walküre, Act I, Götterdämmerung, Act I, Siegfried, Act I.)

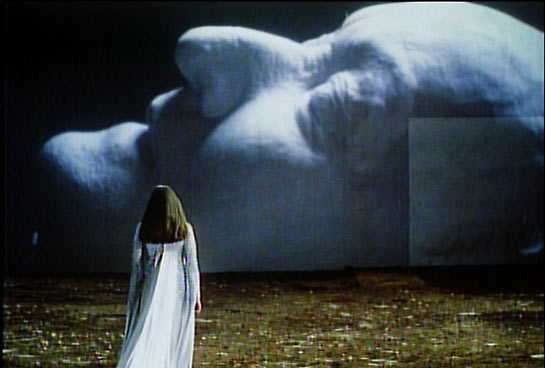

Aside from the musically curious, and adventurous, the audience for that first Ring cycle consisted primarily of European royalty, as well as musical royalty. Kaiser Wilhelm, King Ludwig II of Bavaria, and Dom Pedro II of Brazil were all in attendance. As a matter of fact, the record shows that when Dom Pedro checked in to a local Bayreuth hotel he signed his name as "Pedro," and his occupation as "Emperor." Also staying in Bayreuth and its neighboring cities and villages were the cream of European composers and intellectuals: Anton Bruckner, Edvard Grieg, Peter Tchaikovsky, Camille Saint-Saëns, and Franz Liszt. They all came to pay respect to the master. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and the great Russian author Leo Tolstoy also attended this unprecedented event. Like any other theatrical premiere, the first Ring cycle went through many mishaps. Besides the already mentioned fact that part of the Siegfried dragon was missing, at one point during Das Rheingold a section of the scenery was raised too early only to reveal some stagehands backstage lounging about. Also bass Franz Betz, playing the role of Wotan, misplaced the ring during the Curse and had to run into the wings to get it. Wagner was furious and refused to take a curtain call after the performance even though Rheingold was received with wild applause. And what was the critical reaction to the first Ring Cycle? That first Bayreuth public was judging not just the musical offering on the stage, but the newly-built theater itself where the operas were presented. When it came to the Festspielhaus, the critics of the time found it a revelation. Many praised the seating, which devoid of any boxes, made attending the festival a truly democratic experience. Very few critics made any mention of the lack of any distracting ornamentation inside the theater, but some did enjoy the "novelty" of darkening the auditorium during the acts. We must remember that back then the house lights were always on during performances at every other opera house in the world. The darkening of the auditorium was a Wagner innovation that first occurred at the Festspielhaus, eventually caught on in other theaters, and has continued to this day to be the accepted practice worldwide. The influential music critic of the time Eduard Hanslick was one of the few who commented on the theater's sunken orchestra pit. He called it one of Wagner's most revolutionary ideas. I am sure that Wagner took this comment as an insult to his music. Hanslick had been a great Wagnerian in his youth, but had moved on to champion the music of Johannes Brahms as being the logical descendant of the Germanic cultural tradition of Mozart, Bach and Beethoven. The fact that Hanslick was a Jew really stirred things up as far as Wagner was concerned. Their feud was monumental, with Wagner accusing Hanslick that his style of Jewish criticism was anti-German. Of course, Wagner did not stop there. In his opera, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg the character of Sixtus Beckmesser is a caricature of Eduard Hanslick himself. When the first Bayreuth Festival was over, Wagner began work on Parsifal. It would prove to be his last opera. A somber work filled with Christian symbols and mysticism, but also layered with Eastern philosophy and Buddhism, the idea for Parsifal had been in the composer's mind for decades. Now he was ready, both mentally and financially to finally face up to the project. The majority of the writing took place in Italy, and on this trip he was accompanied by the artist Paul von Joukowsky, who had become a disciple after the first Bayreuth Festival. In Italy, Wagner found such places as the Palazzo Rufolo in Ravello and the interior of the cathedral in Siena as two of the most beautiful sights in Europe. Eventually these places would be transformed into Klingsor's Magic Garden in Act Two and the Temple of the Grail in the second scene of Act One respectively. After Wagner saw the sketches that von Joukowsky completed during their trip, the composer realized that he had found his stage designer for his new work in progress. (Below: a still from the film Parsifal (1982), directed by Hans-Jürgen Syberberg. The majority of the film takes place on, or around Richard Wagner's death mask)

For a complete list of the cast of the first performance of Parsifal, as well as pictures from that production, you can visit the Productions section of this site by clicking here. The composition of Parsifal took four years to complete. During this time Wagner began to realize that the sacred nature of the work in progress demanded a greater degree of protection. This work was special and it needed to be treated in a totally unique way. With the support of King Ludwig, Wagner decided that Parsifal should only be performed at Bayreuth. The King agreed that the work should never be desecrated by contact with any profane stage. If Bayreuth was a cathedral to Wagner's music, then this holy temple was going to have its very own Bühnenweihfestspiel (A Festival Play for the Consecration of the Stage). Wagner finished the orchestral score in January, 1882, and the work was performed sixteen times during July and August of the same year. These performances constituted the second Bayreuth Festival. All performances of Parsifal were conducted by Herman Levi, who happened to be Jewish. During the rehearsal process Wagner urged Levi to submit to baptism before performing the new work. For months Wagner hounded the conductor to accept Christianity. Time after time Levi refused. Wagner never thought of replacing Levi, though, he was arguably the best conductor in Germany, and he knew Wagner's score inside out. The work was an incredible success, and after the close of the festival Wagner and his family escaped to Italy -- to his beloved Venice in order to avoid the dreaded Bayreuth winter, and to rest after the Parsifal ordeal. He was happy and satisfied with his recent work and with his theater, and he knew that keeping Parsifal from being performed in other opera houses would ensure a steady income for his family once he was gone. (Below: the Ca' Vendramin Calergi on the Grand Canal in Venice. This photograph from 1870 was taken by famed nineteenth century photographer Carlo Naya.)

Richard Wagner died on February 13, 1883 at the Ca' Vendramin Calergi, a sixteenth century palazzo on the Grand Canal. He had been ill for some time with heart trouble, and that morning he and Cosima had had a terrible fight about his amorous infidelities. Recently, Wagner had been amorously involved with Carrie Pringle, an English soprano who had been one of the Flowermaidens in Parsifal. There was also Judith Gautier who had been Wagner's mistress since 1869 -- she was 24 and he 56 when they met. Cosima knew about it. It was Gautier who sat next to him for The Ring Cycle, and Cosima had been heartbroken over this. On the day of his death, Wagner cried out at 2:00pm, and while he was breathing his last Cosima went over to the piano and played. Wagner was dead within the hour. He was only 69 years old. There was a funerary gondola that brought Wagner's remains over the Grand Canal. The body was entombed in Bayreuth, in the garden of the family estate, Villa Wahnfried. There is no inscription on the tombstone.

|